Unlocking the full power of synchrony

Imagine personalizing your ventilation strategies for each patient, breath by breath, for more Lung and Diaphragm-protective ventilation (LDPV). Now, to complement our most personalized ventilation modes, NAVA and NIV NAVA, we are introducing Neural Pressure Support (NPS) and Non-invasive Neural Pressure Support (NIV NPS). These unique modes – available as options for the Servo-u ventilator system – have been designed to improve patient-ventilator synchrony in complex and challenging ICU patients in order to provide better outcomes.

Unlocking the full power of synchrony

The diaphragm and VIDD

The diaphragm is in many ways the most important skeletal muscle for the preservation of life, helping to maximize oxygen intake and removal of CO2 to maintain a healthy normalized pH of the blood. Its continuous activity is fundamental for lung, heart and brain function, breath by breath.[1]

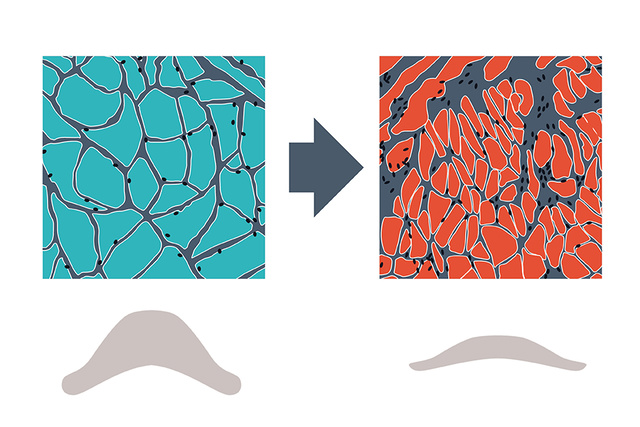

Ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction (VIDD) is prevalent in ventilated ICU patients, and associated with outcome, where diaphragm disuse atrophy due to prolonged controlled ventilation, excessive ventilator support and over-sedation are key factors.[2],[3],[4]

Asynchronies and VIDD

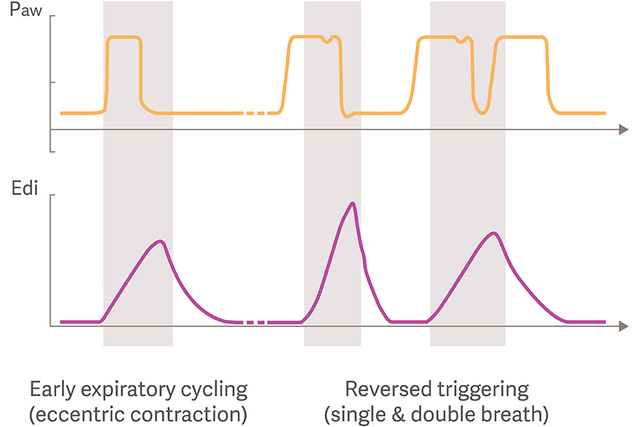

The growing research and recognition of the diaphragm, VIDD and its clinical impact has recently also revealed that early inspiratory flow termination, leading to potentially harmful eccentric diaphragm contractions are frequent during Pressure support ventilation.[5]

Reverse triggering is another frequent type of asynchrony in which the diaphragm is triggered by the ventilator’s passive inflations, which may also generate potentially injurious eccentric diaphragm contractions, and double-triggering.[6],[7]

Respiratory drive, effort and SILI

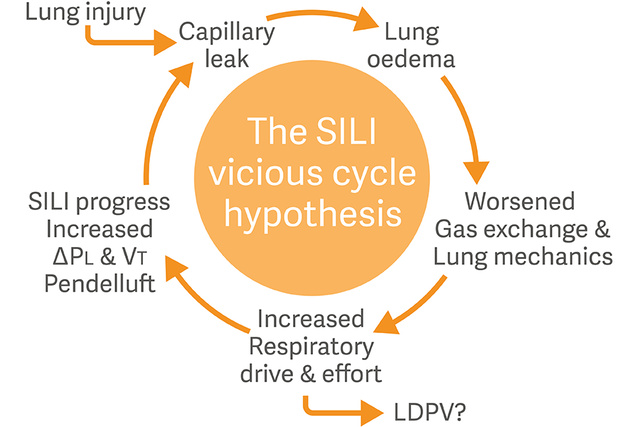

Another concept which has emerged as a major challenge for ICU providers is Self-inflicted lung injury (SILI) where the respiratory drive and effort play unique roles.

When the lung is inflated through a combination of positive ventilator pressure and negative patient-generated pressure, the result may be a harmful lung-distending transpulmonary pressure.[8],[9]

Dedicated monitoring and management of the patients’ respiratory drive and inspiratory efforts are now recommended to minimize risk of SILI.[10]

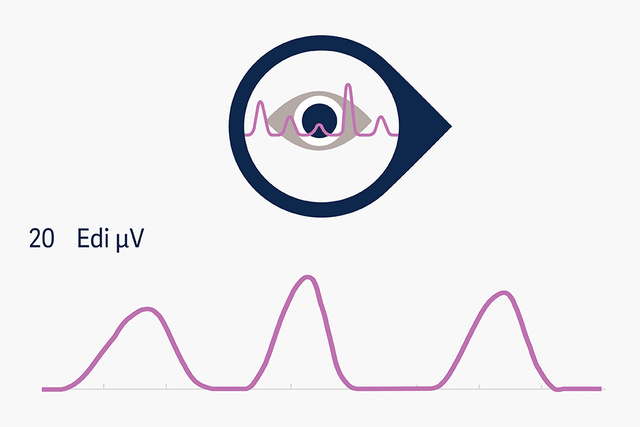

Edi monitoring

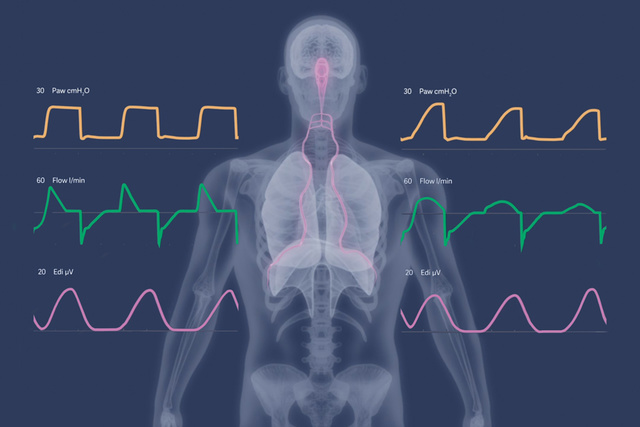

Electrical activity of the diaphragm (Edi) monitoring allows continuous access to the patient’s respiratory drive and has been confirmed as predictor of extubation success, by providing earlier information than conventional weaning parameters[11],[12]

Furthermore, for monitoring of inspiratory effort with the objective to assess lung-distending pressures, new methods based on static and dynamic ventilator maneuvers have been proposed, for future implementation in daily clinical practice.[13],[14],[15]

NAVA and NIV NAVA

A large randomized multi-centre trial, showed that NAVA significantly increased the number of ventilator-free days and shortened the time of mechanical ventilation by almost 35%.[16]

The lung- and diaphragm protective principles in NAVA are that the tidal volume is controlled by the patient’s respiratory center where the delivered inspiratory pressure support is in synchrony and proportional with diaphragmatic muscle activity, which is continuously visible for the intensive care providers.[17],[18],[19]

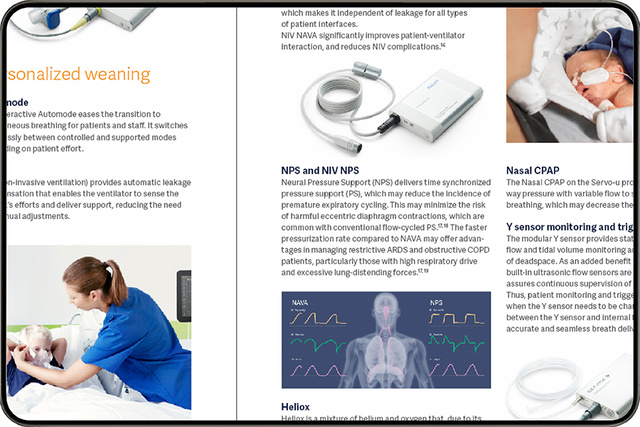

NPS and NIV NPS

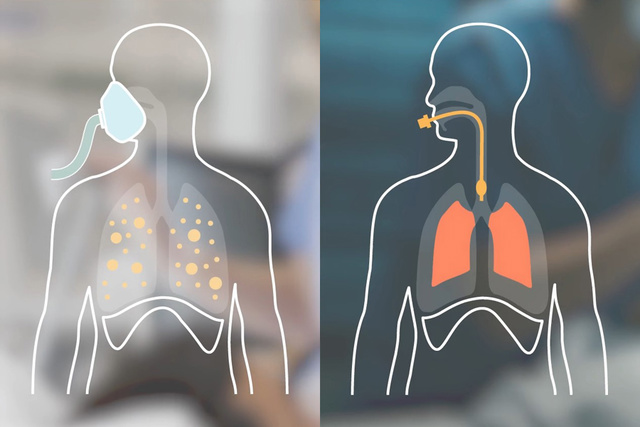

The new NPS modes offer clinicians the opportunity to set PS with neural trigger and breath termination synchronized with diaphragmatic activity. This may reduce the incidence of premature expiratory cycling, and also minimize the risk of harmful eccentric diaphragm contractions, which have been found to be common with conventional flow-cycled PS.[20],[21],[22]

A golden opportunity in both NAVA and NPS, is the principle of real-time titration of ventilatory support to a neural respiratory drive target zone, and safeguard appropriate diaphragm activity.

Restricted and obstructed lungs

Compared to NAVA, the faster pressurization rate in NPS may offer advantages in managing restrictive (e.g. ARDS) and obstructive (e.g. COPD) patients, particularly those with high respiratory drive contributing to excessive lung-distending pressures.[20],[22]

Should the patients’ respiratory drive and inspiratory efforts not self-regulate to achieve lung-protective targets, titration of inspiratory rise time and PEEP may be carefully assessed. Further control of respiratory drive may also be achieved by titration of sedation or neuromuscular blockers.[23]

Combining NAVA and NPS

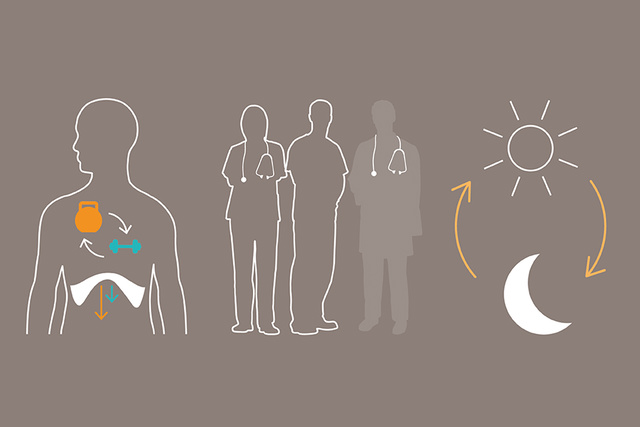

A unique benefit of neurally controlled modes are that they allow for muscle exercise targeting more physiological levels of Edi. NAVA and NPS can be used in intervals with a variation in respiratory muscle unloading, where the training intensity is higher in NAVA and more rest is provided in NPS.[24],[25]

There is also an opportunity to alter the choice of mode during day and night, for example if the ICU is lowered staffed at night with less specialized intensive care providers, who may be less confident to use NAVA compared to NPS.

Implementation

The NPS modes are considered to fill a gap between conventional and neurally controlled ventilation, where the combination of Edi monitoring, NAVA and NPS can be used to facilitate an effective implementation of the technology into clinical practice in a complex and time-pressured ICU environment.

A stepwise implementation approach can now be undertaken where purely Edi monitoring is the initial step, followed by NPS and completed with NAVA being the pinnacle of personalized ventilation.

Literature and Education

Learn more about the benefits of Getinge’s approach to Personalized ventilation and our latest pioneering mechanical ventilation technologies and innovations.

NPS & NAVA training and education

Find out more about the NPS and NAVA modes of ventilation on our Academy Educational website.

The Servo-u ventilator system

Explore the Servo-u eBrochure & discover how our flagship Servo ventilator can support you in the ICU.

Servo-u functionalities

Make the most of your Servo-u with additional functionalities and our latest software options.

Explore our products

Discover more about the Servo ventilator systems